Amongst the extensive kit of cabinet-maker's tools in the 1797 Seaton tool chest1 are two of the relatively rare2 planes known as cock-bead fillisters.

It may be remarked that no positive identification of this tool, in the form of a contemporary labelled illustration, is known but there are several documentary references3 to tools of this name, including the original inventory of the Seaton chest's contents. A process of elimination, comparing the Seaton inventory with the surviving contents, really leaves no other identification possible. So, granted that these specialised fillister planes existed, what was the role for which they were intended?

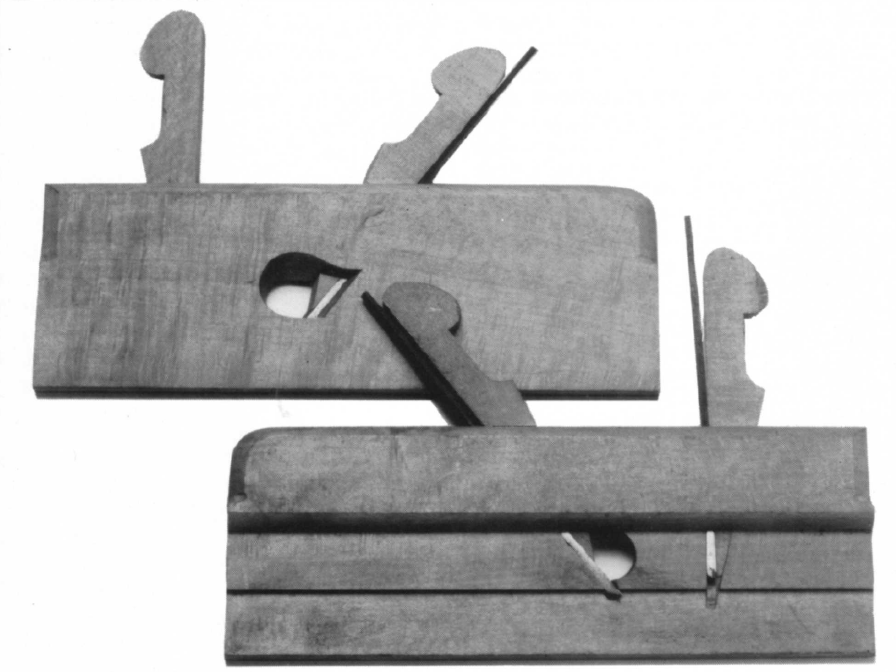

Fig 1

The two cock-bead fillisters from the Seaton chest

Let us first consider their function. A fillister; by definition, is a plane which cuts a rebate or step into the edge of the wood and which has a fence, fixed or adjustable, which limits the width of its cut (i.e, the amount it cuts "on"). In all of the score or more examples of cock-bead fillisters seen by the author, this width of cut is fixed and is very narrow, about 1/8th inch only. On the other hand the planes are capable of cutting "down" quite deeply, a full inch is typical, before their fixed stop meets obstruction. Some examples have adjustable depth stops enabling the cut to be limited to a desired depth. All known cock-bead fillisters have a nicker, a narrow vertical blade which scores a cut line in front of the plane's main blade as the waste wood is cut away This scored line, which establishes the inside edge of the rebate, is valuable when the plane is used across the grain of the timber because it severs the fibres and enables the following cutter to lift the waste cleanly A nicker has little effect when the plane is used along the lie of the grain, and no effect at all when used on the end grain. In the latter case the fibres are standing vertically and the last ones met at each pass of the plane, being unsupported, will break away. From all the foregoing we can therefore deduce that the plane is designed to cut very narrow rebates which may be quite deep, and sometimes at least, it will have to be cut across the grain.

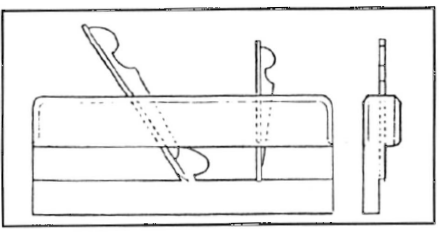

Fig 2

Diagram showing arrangement of cutter and nicker in the plane

This specification appears to meet a particular requirement exactly, namely the cutting of the rebates needed around the front of drawers when these are to be fitted with cock beads, However, practical common sense, supported by the opinion of persons with a lifetime of experience in the cabinet trade, suggests that they would be unnecessary and indeed unsuitable, for this purpose. So, let us consider various stages in the construction and fitting of a cock-beaded drawer.

First, the role of the cock-bead itself. It protects the veneering and cross-banding which was normally found covering drawer fronts during the period when cock-beading was in fashion. It provides a visual definition of the area of the drawer front which is more satisfying than a mere gap, however skilfully narrowed that gap may be. But it also allows the cabinet-maker to make a slight adjustment if his drawer front is undersized (we must remember that material was, until quite recently, more costly than labour and that nothing would therefore be thrown away if it could possibly be adapted for use). If therefore a rebate of uniform width were to be cut around the drawer front (i.e. by using a cock-bead fillister) the application of the bead strip would leave the dimensions exactly as they were, so no adjustment could be made.

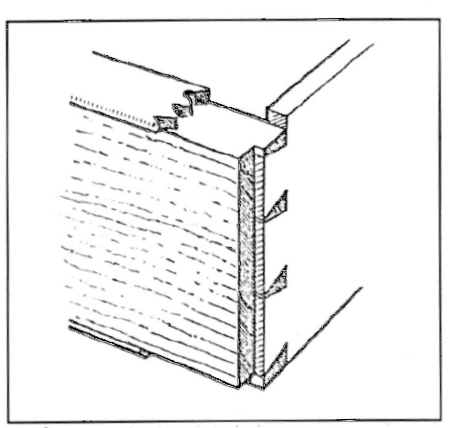

Fig 3

Diagram showing rebates in drawer front to receive cock-beads. Only the

ends and the bottom are rebated. The top bead strip is planed full width.

Then there is the consideration that many drawer fronts in the cock-bead period were not straight. Many for example, were bowed. It is virtually impossible to plane "over a hill", so to speak, since the grain of the wood on the uphill slope is contrary. In any case, for the two longer cuts (the top and the bottom of the drawer front) where one is planing with the grain it makes much more sense to use an ordinary wider soled rebate plane and to work from the edge, i.e. to plane broad and shallow rather than narrow and deep.

This leaves only the short sides of the drawer front where a cock-bead fillister might be supposed to be useful. Even here fear has been expressed that planing down deep, across the grain of the "lap", might hit the end grain of the dovetails, where, as has been explained above, the nicker has no effect, and the grain would break out. In fact the dovetails will always be bolstered by the cross-grain pins enclosing them, so this problem might not arise, but we are still left with the biggest problem of all!

However carefully a rebate plane is held up against the work it tends to creep away from it. This is one reason why a joiner's sash-fillister has its fence bearing against the far side of the job thus locking the cutter solidly up to its cut. But, with the hand controlled cock-bead fillister, the rebate will become narrower as it deepens. The narrower the cutter and the deeper the cut the worse this effect will be. A rebate made in this way would need repeated correction with another plane working in from the side. So, the question is inescapable: Why bother with cock-bead fillisters at all?

The answer, I think, must be that competition in the tool-making and tool-dealing trades, combined with relatively increasing prosperity in the artisan classes, was already by the second half of the 18th century leading to the spread into the mass middle market of the technique used since time immemorial for separating the rich from some of their money, namely selling them things they didn?t want. If it is claimed that a practical, hard-headed and hard-working workman would never fall for such baubles, consider the proud parents of a promising apprentice. That splendid chest the boy was working on every evening just had to be filled, and to include all the latest "improvements." Perhaps it is not mere chance that the era of the cock-bead fillister coincided almost exactly with the era of those great tool chests, approximately 1770 to 1830.

Postscript

If it was not with cock-bead fillisters how were those rebates worked? The natural answer is that they were sawn. Sawing is in fact always the preferred method, whenever it is feasible, but, before the general introduction of circular saws, length was a limiting factor A six foot board would have to be rebated with a plane, but for a cut of no more than 7 or 8 inches, like a drawer side, the job could be done just as accurately and much faster with a back saw. This is surely how the full-time and life-long cabinetmaker would have done it - while his cock-bead fillister, if he had ever had one, nestled safely in a compartment of his magnificent chest.

Footnotes

1 See The Tool Chest of Benjamin Seaton, The Tool And Trades History Society, 1994, page 35. See also John M. Whelan, The Wooden Plane, its History, Form and Function, Astragal Press 1993, page 204 Fig 10:51.

2 Amongst the cock-bead fillisters which have appeared in collections or sale-rooms in recent years are examples by the following makers

Anderson, Leeds 1794-1822

Bewley Leeds 1785-1847

Furse, Exeter probably c.1846

Gabriel, London 1770-1822

Green York 1768-1829?

Moseley, London c.1805 onwards

Nelson, York or London 1750-1852

Turner, Sheffield 1841-1912

3 Documentary references to cock-bead fillisters.

The Gabriel lists 1793 & 95, See Furniture History Society journal 1981

The Sheffield List 1816, item 725.

This article by Gwynne Travis first appeared in TATHS Journal 9, 1996.