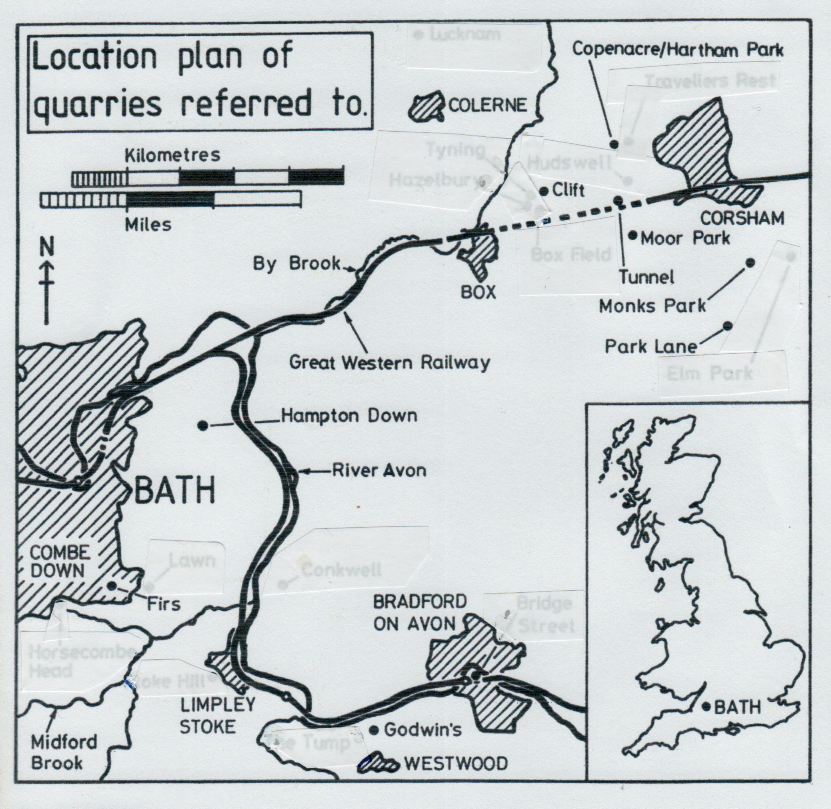

This account sets down most of what is known on this topic and has been written in the hope of obtaining some useful feedback. Bath stone is a relatively soft oolitic limestone of Jurassic age, Its older name of freestone means it can be freely worked by hand tools; there is no plane of cleavage.

The stone is not found at Bath, but occurs to the south and east of the City, mainly in Wiltshire; most workings are underground.

The writer knows of no written account that describes quarrying with saws in Bath stone quarries earlier than 1862, but the archaeological record shows that several types of saw were used from the early eighteenth century onwards. Underground all saw cuts look the same when the light source is perpendicular to the sawn surface, but a light source positioned in the plane of the cut reveals sawing marks characteristic of the type of saw used. These marks result from the interaction between the stone – especially if there are hard patches in it – the profile, pitch and set of the saw teeth and the depth and stiffness of the saw blade.

Frame saws

Early illustrations of stone cutters depict a shallow-bladed frame saw very similar to that of a carpenter's saw, which it no doubt evolved from. The frame is in the shape of a squat letter H; the shallow thin blade was fixed between the bottoms of the uprights and tensioned by a twisted cord and stick between the tops of the uprights. Metopes of these can be seen on numbers 11 and 21 The Circus, in Bath. Hasell's print of 1798 of an open quarry near Bath shows a quarried block being cut with a frame saw. Elsewhere Pyne's Microcosm of 1808 depicts a stone block being sawn with this type of saw. They were used well into the twentieth century to dig block stone in the sandstone quarries in the Selsfield district of Sussex.

Sussex frame saws

Quarrying with frame saws in a Sussex sandstone quarry early 1900s.

To accommodate one of the legs of the frame it was necessary to pick

a vertical rectangular hole or slot to the bottom of the bed being cut.

Note the poles and lines used to help keep each saw upright.

In the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, frame saws were used by stone cutters working in the underground Combe Down quarries to cut up quarried block into products such as ashlar and copings; these saws were sometimes used to cut stone from the rock. The frame saw was a cumbersome tool; the frame and its height made it unsuitable for digging stone underground. However they were sometimes used where the frame could straddle the stone being cut. In Firs Quarry and in one of the Hampton Down quarries there are a few surviving frame saw pillar cuts. The saw marks are distinctive and unlike the ripple marks made by the later frig bob saws, the saw cuts are often concave indicating a shallow blade.

Frame saw marks

End of a small block showing sawing marks made by a frame

saw – the block is resting on its top surface. The location is

in the southern extremity of Firs Quarry on Combe Down

and dates from before 1727.

Pillar ripple mark

A pillar saw cut showing a ripple mark characteristic of a

frig bob, the direction of sawing being towards the camera.

The location is in Firs Quarry on Combe Down.

Two man saws

Another type of stone cutter's saw was the double-hand bellied saw which, apart from its teeth,was similar to the two man crosscut saw used for sawing timber. The foreground of Thomas Malton's 1765 water-colour of the Royal Crescent, Bath depicts working masons with their tools which included a two-man bellied saw, identifiable by the profile of its teeth as a wood saw. Jackson's 1824 'View of the Park Place' at nearby Bristol depicts two masons sawing with a double-hand bellied stone saw. This type of saw was more manoeuvrable than a frame saw, but it also had to straddle the stone being cut through and had the disadvantage of needing two men to work it. As yet there is no evidence of their use in the Bath quarries.

Could these saws have been used for sawing into the rock underground by one man? Their blades are light, thin and not stiff, and the cutting edge has a fish belly shape. These features would have been unhelpful, but it may have been attempted. It was done elsewhere, double-hand bellied stone saws including some adapted to one man operation were used to dig and cut up block stone in the coralline limestone quarries in Bermuda.

A Bermuda Quarry

A well known postcard view of a Bermuda stone quarry, the

saw appears to be a bellied two man saw that has been modified

locally for one man use. The rock face clearly shows evidence of sawing.

Bermuda stone cutter

A Bermudan stone cutter sawing ashlars with what appears to be

a bellied two man saw that has been modified locally for one man

use. The stone cutter's flared trousers suggest a mid to late 1960s date.

Early one-man rigid blade saws

In a few quarries there is evidence mainly in the form of pillar saw cuts that show that one-man, rigid-blade saws were used, albeit as an addition to the prevailing method of digging with wedges and chips, from circa 1810 to circa 1830.

The bulk of these early pillar saw cuts are in the northern part of Byfield Quarry; some of these sawn surfaces have dateable graffiti written on them. The following dates have been recorded:– 1814, 1818, September 21st 1823, March 22nd 1838, 1840 and 1845; the graffiti may be much later than the sawing. The longest saw cut seen by the writer was 5 ft 10 inches (1.78 m) long indicating a saw length of around 7 ft (2.1m). Other more typical saw cut lengths of 3 ft 9 inches (1.16m) and 3 ft 4 inches (1m) have been noted. The latter saw cut exhibited score marks made by the saw teeth when the saw was withdrawn vertically from the saw cut: the pitch of these score marks is 35 mm indicating a blade with widely set teeth at a pitch of 11/16 inch (17.5 mm). Similarly in the adjoining Firs Quarry, graffiti dates of Feb 18th 1831 and May 19th 1841 have been recorded on sawn surfaces. Some of these sawn surfaces show marks that cannot be matched to any known type of saw.

The only other saw cut falling into this period known to the writer is at Godwin’s Quarry at Westwood. Dated May 1827, this cut was made by a saw blade no deeper than 51/4 inches (146 mm) and was probably very short.

Frig bob saws

The single-hand stone saw known to quarrymen and masons as a frig bob typically had a heavy rigid blade ranging from 5 ft to 7 ft (1.5m to 2.1m) long and when new was 9 inches (225 mm), or more, in depth with a peg tooth profile teeth at a pitch of 5/8 inch (15.87 mm).

For sawing blind cuts in the rock, it was found advantageous to file in an extra tooth or two around the front of the saw. At the other end an eye hole attachment was riveted to the blade – a simple ash stick inserted in the eye hole sufficed for a handle.

When were frig bobs first used in the Bath stone quarries? The very late 1830s seems probable. Work began on Randell, Saunders & Co’s Corsham Down (Tunnel) Quarry in 1839. A careful search of the area around the foot of the slope shaft in 2006 only found evidence of cutting with frig bobs. In Godwin’s Westwood Quarry a “May 1840” graffito conveniently dates the first frig bob sawn pillar. A sale of railway contractors plant at Box held in August 1841 included stone saws and other quarry tools. At Farleigh Down Quarry an “1845” graffito written on an early frig bob sawn pillar could suggest that the changeover to sawing varied from quarry to quarry by several years.

Frig bob saws were also used at Dundry Somerset around c1855, at Beer Quarry, Devon from the late 1880s and at Weldon Quarry, Northamptonshire, also from the late 1880s. Although saw cuts were started by sawing horizontally, the saw was quickly worked into a sloping mode so that the front end of the saw cut was deeper than the back end. To prevent the saw dust from clogging the saw, it was necessary to add water from a drip tin. This was usually an old tin with a small hole in the side just above the bottom – a match stick placed in the hole conducted the water to the saw cut. The resulting slurry was swilled out of the cut by the back stroke of the saw.

The hardness of Bath stone varies between the different beds and quarries; roughly it took an hour to saw a vertical depth of 1 foot over a length of 5 feet or so. In the mid 1950s drills powered by compressed air were introduced to two quarries. It was found that by drilling a series of deep holes at roughly 3 to 4 inches pitch along the line of an intended saw cut, that hand sawing was greatly speeded up. This practice ended with the closures of Hartham Park Quarry in 1960 and Clift Quarry in 1968.

The sawyer stood or sat directly behind the saw blade which was lined up with the middle of his chest. The saw was held with both hands and the effort shared equally by both arms. But this symmetrical mode was not possible when sawing pillar cuts: the arm nearest the pillar did more of the work. Pillars of unhewn stone are left to support the ground above.

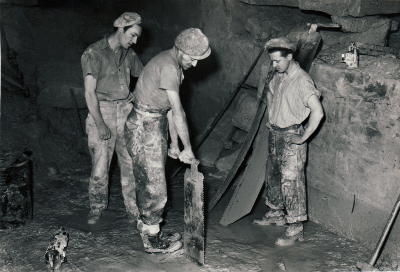

Frig bob sawing

Marshall Cole the ganger (LH) and Reg Pashley (RH) sawing with

frig bobs at Hartham Park Quarry in the 1950s.

Frig bob vertical

Jack Osbourne sawing vertically with a frig bob, note the back of

the saw is sliding against a pick head, his feet are standing on

the pick helve. Hartham Park Quarry 1950s.

New pillar cuts were offset by a few inches to give clearance for the saw handle and the sawyer’s hand. This offset is known as a hatch. To prevent chaffing against the pillar, sawyers wrapped a strip of cloth or a short length of old bicycle inner tube around the knuckles of the hand nearest to the pillar. To avoid the stone breaking off short when it was subsequently raised, i.e. wristing off, it was necessary, when making a pillar cut, to aw to the bottom of the bed without taking a break.

Frig bob saw-teeth needed regular sharpening and setting, For sharpening the saw was inserted upside down into a saw cut in the top of a saw stone or bench; the sharpening was done with a triangular file, starting at one end of the saw, filing one side of each tooth in turn with one pass of the file until the other end of the saw was reached. The saw was then turned around and the process repeated on the other side of each tooth. The front angle of the teeth was filed straight across at right angles to the blade. The files were supplied by W. Tyzack, Sons & Turner, Ltd. of Sheffield. Sometime in the early post war period a saw sharpening machine was bought from Thomas Robinson & Sons Ltd of Rochdale, this machine used a veeprofile carborundum wheel to sharpen the teeth.

Saw Sharpener

The vee profiled carborundum wheel of the Thomas

Robinson & Sons Ltd saw sharpening machine.

Repeated sharpening over a long period reduced the depth of a frig bob to around 4 inches (100 mm), this was then known as a razzer or bacon slasher; razzer is believed to be a dialect word meaning worn out. These worn saws had a specialised role for making saw cuts in the jad (the horizontal slot picked out under the ceiling and above the stone being sawn).

Frig bob & razzer

Keith Palmer holding a razzer (left) and a

frig bob (right), note the opening hammer

lying on the floor. Keith started work in Clift

Quarry at Box in 1968 and spent his first

two weeks sawing with a frig bob.

Razzer in jad

Starting a back cut with a razzer, the quarryman is sitting

in the wrist hole vacated by the wrist stone; Hartham Park Quarry 1950s.

For setting the teeth, i.e. splaying the teeth slightly outwards in alternate directions so that they made a cut a little wider than the thickness of the blade, the saw teeth edge of the blade was laid along the head of a rail. The rail acted as a former whilst every other tooth was opened or bent outwards with an opening hammer. The saw was then turned over and the process repeated on every other tooth. This gave clearance so that the main part of the blade was clear of the sides of the cut. Care was taken to work from the base of the tooth towards the point to avoid breaking it. The opening hammer seems to have been a locally made tool.

Opening hammer

Setting the teeth with an opening hammer

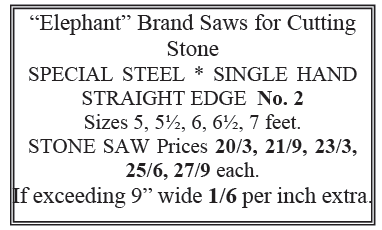

There are a few references to suppliers and makers of stone saws.

In a series of three advertisements addressed to Quarry masters and Builders, G T Robbins, a Bradford on Avon ironmonger, advertised cast-steel stone saws on 27th March 1875.

The Winding Up Accounts of Randell Saunders & Co. Ltd includes two payments “For Saws”. In 1887 they paid £8-7-3d to G & T Gray and in 1888 £10-15-6d was paid to Spafford & Co.

Throughout the 1890s, the Directors of the Bath Stone Firms Ltd authorised payments to G & T Gray, A Spafford & Co and W Tyzack, Sons & Turner Ltd, what the payments were for was not recorded but could have been for saws and saw sharpening files.

Early Sheffield directories list several members of the Gray family engaged in the metal trades. Thomas Gray was a saw maker in 1834, a scissor smith in 1839 and a saw manufacturer in 1841. George Gray was manufacturing pen knives in 1839 and 1841, and Jonathan Gray & Sons were manufacturing saws at 36 Malinda Street in 1841. By 1849 George and Thomas Gray were trading as saw manufacturers at 36 Malinda Street, also known as the Australia Saw Works from the 1880s, in 1901 their products included files. G & T Gray were incorporated with John Elsworth & Sons, Ltd. around 1905, but the G. & T. Gray name continued to be listed until 1923, at least.

Abraham Spafford was listed amongst the gentry in 1834, as a bookkeeper in 1841 and as a saw manufacturer in 1849. A Spafford & Co were recorded at several addresses but by 1879 were at the Imperial Works, Brown Street. Between 1901 and 1923 saws ceased to be listed as a product, they appear to have had a wide product range and also were making files in 1901.

An item in a recently acquired 1932 catalogue of W Tyzack, Sons & Turner Ltd (above) confirms that they also made frig bobs which they described as stone saws, single hand. When this company began and ceased to make this type of saw is not yet known.

Quarrymen and their gangers owned their own tools. It appears that the quarry masters and firms bought the saws in batches and sold them to the men; this practice ended in 1939. The above prices represent a big portion of the fortnightly wage of a Bath stone quarryman in the 1930s.

Digging of Bath stone stopped in September 1939 and resumed in 1945 after the war ended; mechanisation soon followed. Three Mavor & Coulson arc shearers (basically tracked chain cutters) were delivered to Moor Park Quarry in 1948 to cut block from the rock. However these could not sever the back of the block from the rock and frig bobs were retained for this task.

Moor Park closed in 1952 and its equipment was transferred to Monks Park Quarry where the same practice continued until sometime around the mid 1950s when compressed air power was introduced. It was found that blocks could be snapped off at the back by a single set of plug and feathers inserted in a hole drilled in the natural parting under the bed at the front of the block.

At the Hartham Park and Clift quarries, it was found that, by drilling a series of deep holes at roughly 3 to 4 inches pitch along the line of an intended saw cut, hand sawing was greatly speeded up. This practice ended with the closure of Hartham Park in 1960 and the Clift in 1968. Park Lane Quarry was the last to be entirely hand worked; it closed in 1958.

Frig bob saws continued to be used by masons, it was still possible to buy them from Avery, Knight and Bowler Ltd of Bath as late as 1992 at a reputed price of £100 each – they now no longer sell them. However in 2006 the writer found an almost good as new one in a reclamation yard, which he secured for £20!

This article by David Pollard first appeared in TATHS Newsletter 101, Summer 2008.